I had come to lino the long way round, after a couple of decades living in the clean, safe land of digital art. I was never a fan of computer-generated lines and flat colour fields, and had always used my digital tools much as you would use a pencil or paints – but still, mistakes could be undone. Edit-Undo was always there to save me.

So when I switched over to the physicalities of linocut printmaking, the greatest adjustment was losing that Edit-Undo option. You can reach for an eraser to rub out your pencil line, but you can’t uncut that line when your gouge slips. What’s done is done. It’s like life. You can’t unsay what you’ve said, unbreak your arm, or uncrash your car. It’s real. It’s risky. And it feels like a miracle when it works out.

It’s a great feeling, pulling off those miracles. And it wouldn’t feel so great if you could just pop polyfilla in the mistakes and make them go away. So I’m glad it didn’t work. I’m glad the mistakes are for real; unretractable and totally human.

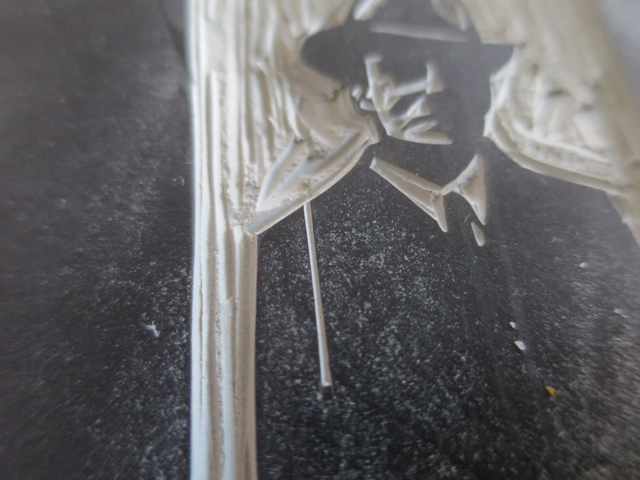

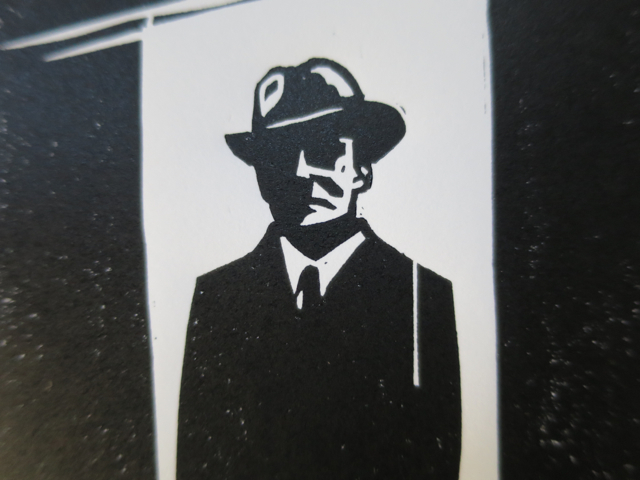

Sometimes a mistake is so bad that you have no choice but to bale, and start again, as with my dapper gentleman here. But sometimes it’s just enough to let the viewer know that what they are looking at is real life. There’s a name for that. It’s called an “honesty mark”. It’s the wobble of the trapeze artist that makes the act doubly exciting. It’s the double-fault of the tennis player as she struggles for a nail-biting moment to retain control.

I’ve told you about Victorian art critic John Ruskin before, and I will turn to him again. In The Stones of Venice, he had something very beautiful to say about imperfection:

“It is the sign of life in a mortal body, that is to say, of a state of progress and change. Nothing that lives is, or can be, rigidly perfect; part of it is decaying, part nascent… And in all things that live there are certain irregularities and deficiencies which are not only signs of life, but sources of beauty. No human face is exactly the same in its lines on each side, no leaf perfect in its lobes, no branch in its symmetry. All admit irregularity as they imply change; and to banish imperfection is to destroy expression, to check exertion, to paralyze vitality. All things are literally better, lovelier, and more beloved for the imperfections which have been divinely appointed, that the law of human life may be Effort, and the law of human judgment, Mercy.”

You can get lino laser-cut, apparently. Although why you’d want to, I don’t know. I offer hand-carved rubber stamps in my Etsy shop, and because of the time it takes me to cut the tiny detail with all nerves tingling, I’m sure I charge more than you would pay to have a machine do it with more precise results. And yet, people want mine.

They get that a few slight imperfections make it more beautiful. They get that the human effort invested makes it into something special. So I will keep striving for perfection, and failing, like all humans do. And I’m glad that I can’t hide behind the polyfilla. My linocuts are the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. So help me God.