This blog post is not about pubic hair. I have to say this upfront because 19th century art critic John Ruskin is famous for being so shocked at the reality of his wife’s body (as opposed to all those silky-smooth marble sculptures he was used to), that after five unconsummated years, Effie Gray had to look elsewhere for satisfaction.

Poor Effie. Poor John. But now try to put that out of your mind, because Ruskin had a lot of powerful things to say about art, architecture and society which resonate perhaps even more today than ever. His Seven Lamps of Architecture made a big impression on me years ago, when I was grappling with the swing in contemporary art towards an aggressively anti-craft stance.

I had always loved things made with patience, care and years of practice, and yet, the art world was showing great disdain for the slow, deliberate exactitude of craft. It favoured pure ideas, and if these ideas had to be made concrete, then their execution was intentionally sloppy to distinguish them from the base hobbyism of ordinary housewives at their kitchen tables. As an art critic, I played along, but it made me uneasy.

Ruskin spoke of the Lamp of Sacrifice. This was one of his seven pillars of architecture: the beauty bestowed on a building through the human time spent making it; the transformative power of long hours spent carving intricate decoration, even round to the back of the columns where no one will see. “It is not the church we want,” he said, “but the sacrifice; not the emotion of admiration, but the act of adoration: not the gift, but the giving”.

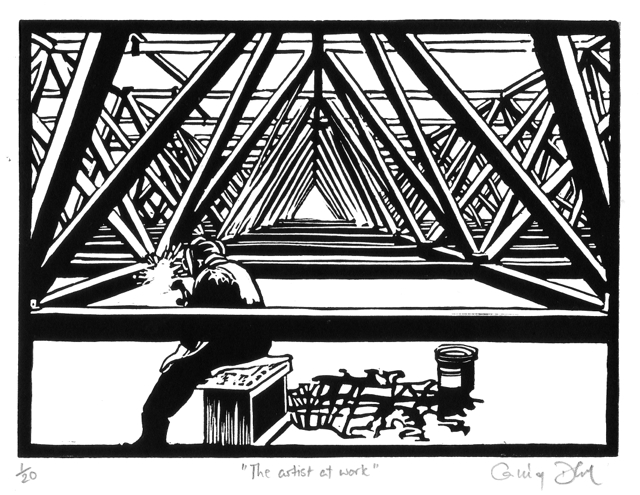

I loved that concept as a student, and I held onto it throughout my years of art criticism, knowing that I was not wrong to value craft, and quiet labour, for its own sake. But now, as a printmaker, who spends hours in quiet contemplation as I cut with my 0.5mm gouge, sliver by tiny sliver, through blocks of lino, I really get it.

Last week I spent six hours cutting a 7×5” composition, fully focussed on the intricacies of the Escher-like architectural structure. One lapse of concentration and the composition would collapse. Within this image was the figure of a welder, also focussing on his task within the monumental structure. He sat there alone, quiet, patiently fusing the metal on one of thousands of corner joints. I developed a sore wrist. I’m sure he had a fair few aches and pains too.

Over the course of cutting this image I became fused in my mind with this welder, both of us taking our time, doing our best, methodically working through the thousands of details we had ahead of us to do our bit on this imposing building. I felt physically connected to Ruskin’s idea that architecture gleans power from “the perception or conception of the mental or bodily powers by which the work has been produced”.

Ruskin was writing in the mid-19th century, when the industrial revolution was more or less complete. He was no fan of mass production. He was against the division of labour, where workers were denied the pleasure of creating a whole product “so that all the little piece of intelligence that is left in a man is not enough to make a pin, or a nail, but exhausts itself in making the point of a pin, or the head of a nail”.

Nothing beats the pleasure of learning to make a whole thing yourself, from start to finish, something out of nothing. I live for that pleasure. To take back the means of production, as Marx would have it, and feel the power of being truly able to do things for yourself instead of paying The Machine to spit them out for you, with all the hidden social and environmental damage that entails.

“The workman ought often to be thinking,” argued Ruskin, “and the thinker often to be working, and both should be gentlemen, in the best sense.” He saw class divisions deepening, society separating into “morbid thinkers, and miserable workers”, and he proposed a solution which I know is true for me:

“It is only by labour that thought can be made healthy, and only by thought that labour can be made happy, and the two cannot be separated with impunity.”

My welder print started as an interesting technical challenge with an Amsterdam angle – based on a photo during the building of the RAI in 1968. But by the time I had finished it, a title had floated to the surface of my mind: “The artist at work”. And I knew that I had to go back and read Ruskin again.

You can buy the original handmade linocut print, one of an edition of 20, here.